(Not him, obviously. But weren't the 80s ghastly, though?

Leggings and miniskirts, oh my.

And a headband, no less!)

Leggings and miniskirts, oh my.

And a headband, no less!)

In what seems to be becoming a regular feature here, today's featured religious* is the Venerable Mère Marie de l'Incarnation, 1599-1672, who started out this life in Tours and departed it in an Ursuline convent in New France, which is alot like Québec only with a great deal fewer Frites-Alors, much less poutine, and not even close to as much or as many habitant and habitants.

Both sides of my family, the French ones and the English ones, came over to North America early. This could mean they were desperate, adventurous, bored, reckless, in danger of incarceration, excessively fond of lengthy boat travel, or all these in varying measures. I know a lot about the English side: they fought in the Revolutionary and Civil Wars and sent letters telling about this. I know less about the earliest French arrivals, and I suspect it is because they are the ones who gave the women in our family the facial hair, and the less known about them, the less rancour towards the dead will arise. Still, though, I love the history of Québec/New France/Nouvelle France as much as I love that of the Ottoman Empire and Turkey, so while rummaging around online for stuff about the former, I was reminded of the story of the Filles du Roi, in which the above Mother Marie played a part.

(The Roi Whose Filles We're Talking About.

(The Roi Whose Filles We're Talking About.Somehow this style never caught on in Trois-Rivières.

They were still probably wearing headbands.)

Firstly, it should be said that Filles du Roi are not at all the same as filles de joie, who figured in earlier posts and had far better wardrobes, not to mention restaurant choices, even after Escoffier, than the habitants of the Canadian wilderness.

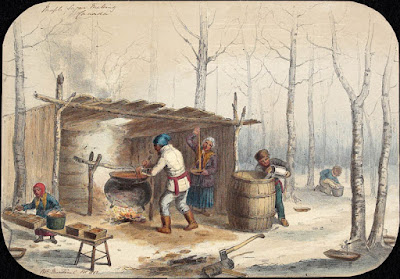

(As you can see from the rug and the furniture

(As you can see from the rug and the furniturein this painting by honorary Canadian Cornelius Krieghoff,

imported spouses were also forced to endure shopping at Ikea, which was

even more horrific when Karl XI

was in charge of Sweden

was in charge of Swedenthan it is now.)

Unlike filles de joie, Filles du Roi were not career women; their job - once they moved to the New World and found a husband (which tended to happen within a month or so after disembarkation) - was to be a wife and mother, which, alongside religious and camp-follower, was one of the three main career trajectories available to women at the time. Despite the arduous passage across the Atlantic, New Franceian Hausfrau could well have seemed the middle-ground option for marriageable girls with a moderate, though not overweening, sense of adventure and a similarly underwhelming set of marriage prospects.

The Filles du Roi were recruited and imported from 1663 to 1673, beginning in northern cities like Paris, Rouen, and New Rochelle. The purpose of the programme was to populate the colony, which would eventually provide new soldiers to defend France's holdings against Iroquois and English alike. Moreover, having a wife, family, house, land - not to mention livestock, two barrels of salted meat, and dowry from the King - would in theory serve to keep more of the colony's male population where they were instead of following the trend of leaving New France to return home after their three years of service. Though there were only 700, or 852, or 1000 women shipped in during those years, the French population of New France was itself only about 2500 in 1663 (as contrasted with English North America, which already had 100,000 inhabitants), with only 1 percent of New France territory being used by the settlers, so the resulting marriages and considerable progeny (you only got a 300-livre annual pension if you stalled at 10 children, but 400 if you made it past a clean dozen) could indeed eventually constitute a relatively significant bulwark against English encroachment once the children reached soldiering age. In 1671 alone, about 700 babies were born to the new families, and by the end of the ten-year importation of Filles du Roi, the sex ratio in Nouvelle France was more or less even. By 1754, at the start of the Seven Years' War, or the Fourth Intercolonial War, or the Guerre de la Conquête, or the 'French and Indian War,' the 'Indians' at least had some Frenchmen to fight alongside them.

All that notwithstanding.

Some of the girls were not as ready for the privations of Canadian homesteading as were others. They got a quick remedial education in whatever practical domestic arts they lacked while awaiting introduction to suitable suitors, plus a ration of pins, needles, thread, taffeta, and scissors among other things. They did not, however, receive a pair of Sorels or experience in wood-chopping or fence-building. Just as the Filles preferred garçons who already had une habitation set up and ready for move-in (look, I love the Canadiens as much as you do and, honestly, probably more so, but that really is the boring reason they're called The Habs: steady settlers with land and a cabin. Homesteaders. Pea soup. Stability and stoicism, not high-sticking), the male colonists were in need more of a sturdy helpmeet than a piano-playing bourgeoise.

Enter Marie Guyart the Ursuline.

(And also another entry, since this one got away from me.)

*And for the irreligious among you, 'religious' in the nominative way is different than the adjectival version. Flat-earthers, for example, or snake-charming charismatics, no matter how ardent their faith in their faith, would only be adjectivally religious, i.e., religious people, a religious population, rather than 'a religious' like Mother Marie, who took vows/joined an order/consecrated her life. It's not biased language, I assure you, and it certainly doesn't prove the earth isn't flat.

No comments:

Post a Comment